It’s a small museum with a big mandate.

America’s Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee is far from the South where lynching and slavery were most common, but physical distance does not dilute the powerful message against racism presented by this small centre.

James Cameron, who founded the museum, was the only known survivor of a lynching in the United States until his death on June 11 at the age of 92. He fought against black oppression on a variety of fronts throughout his life and memorialized his experiences in the museum he started in the basement of his home in 1988.

In 1930, Cameron and two friends were falsely accused and jailed for murder of a white man in Marion, Indiana.

A mob of thousands gathered around the jail and the three were dragged outside. Cameron’s two black acquaintances were hanged, and when a noose was placed around his neck he thought his fate was also sealed.

However, someone in the mob declared Cameron’s innocence and he survived to serve a four-year jail term for accessory before the fact to manslaughter. After he was freed, he worked at various jobs, went to trade school to become an engineer and became politically involved in the civil rights movement. He became recognized for his lifelong efforts to defeat racism.

“It took 63 years for the State of Indiana to pardon him,” said Bethany Criss, community partnership coordinator at the museum, during an interview. “They pardoned him because it was a bogus charge. It was something that was a completely unrealistic charge, something that couldn’t be validated in modern understandings of the law.”

Cameron’s museum proposes that the black holocaust began with the capture of Africans and their enslavement in the U.S. and that it still exists to this day.

“A holocaust is a genocide and genocide is a destruction of a people, not just through murder but through cultural destruction and intellectual destruction,” Criss said.

“As long as there’s racism in society then this holocaust is going to continue and that’s why we’re here. We want to educate people about the evils of racism.”

Almost four million people were freed when slavery was abolished in the United States in 1865, but being legally free was not the same as being released from the shackles of racism.

In the south, whites instituted “Jim Crow” policies in 1877 to strip blacks of rights gained during the 12-year Reconstruction period at the end of the Civil War. These laws governing segregation came into effect to keep blacks and whites separate. Taxes and literacy tests were used to discourage blacks from voting. The Ku Klux Klan, a white supremacist group, terrorized and intimidated them.

Almost 3,500 blacks and 1,300 non-blacks were lynched between 1882 and 1968. Lynchings were recorded in all but six states, with the majority occurring in the South.

The museum takes a broad perspective on racism.

“Racism is not just a problem localized in the South,” Criss says. “Racism is a problem that’s concentrated throughout the entire world. To think that it’s localized in one region, well, that’s part of the problem that we want to address.”

The museum includes exhibits on African culture, slave ships, slavery, lynching and the history of the civil rights movement in Milwaukee.

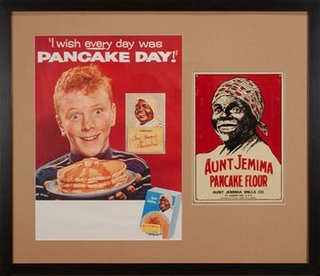

A touring exhibition focusing on the Jim Crow era of segregation from the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia in Big Rapids, Michigan, entitled “Hateful Things” is on show until August 26, 2006.

The character “Jim Crow” was created in the early 1830s by a white actor named Thomas Rice. “Daddy Rice” performed a song-and-dance routine in blackface with the lyrics “Jump Jim Crow.” The expression became a racist term used to refer to African Americans.

The items in the exhibit, which date from the late 19th century to the present, made it seem socially acceptable to mock black America, Criss said.

“Lots of those same images were around at the time that those lynchings were occurring, so you see they are directly connected to this concept of black America as less than human, something less than equal.”

The exhibit includes images of Aunt Jemima pancake flour. Aunt Jemima represents the stereotypical “mammy caricature” of black women: an asexual, ignorant caretaker whose only role in life is to serve others, Criss explained. Although Aunt Jemima’s appearance has undergone changes over the years in an effort to make her seem more politically correct, she remains a caricature, Criss said.

“The overall problem is the ideology behind the creation and the use of marketing a black image in such a fashion. No matter how they change Aunt Jemima’s image, it’s based in racism. It’s based in a racist depiction of black people and that’s why it’s in the ‘Hateful Things’ exhibit.”

Artifacts celebrating Cameron’s personal achievements are also on view in the museum. His pardons from Marion and the State of Indiana and his honourary doctorate from the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee for his work on race and racism are also displayed.

For Criss, the most important item from Cameron’s mementos is an enlarged replica of the June 2005, apology made by the U.S. Senate for never passing an anti-lynching law. Cameron, along with 200 relatives of lynching victims, was in Washington, D.C. to receive the apology.

If someone were to be lynched now it would most likely be prosecuted as a hate crime, Criss said.

“Even though there are no anti-lynching laws today, the significance does not die. It’s still important that on some level, the government acknowledged that they were somewhat, partially culpable in not having protected its citizens. That’s the huge importance of that apology.”

As for the future of the museum, Criss has no doubt that it will continue to be a focal point in the historic neighbourhood of Bronzeville, which was once the hub of black life and culture in Milwaukee. The museum plans to broaden its scope “to be more inclusive for all generations so all generations can reflect on this history.” ~