When my grandmother was a girl she often hitched her sled onto the back of her father’s sleigh so she could glide along behind him when he was transporting a load of wood.

I don’t know if my great-grandfather Daniel Nickerson sold the timber to the local sawmill or if he used it for firewood.

Vera Grace Mollins lived on a farm on the Dorchester Road (now the Scoudouc Road) in Shediac, New Brunswick with her siblings, her father and her mother, Eliza Nickerson (nee Armour).

Unfortunately, my great-grandmother Eliza, who was born in 1863, died of typhoid fever in 1908 when my grandmother was only 11 years old.

The family was poor. At Christmas, my grandmother would put a plate out for Santa Claus, rather than a stocking. Some years she would wake up to find an orange on it, but other years, all she got was a lump of coal — or so she told me.

Not only did she help collect the wood, but she also planted potatoes. She once showed me how.

She also taught me to crochet.

In her early career, she was a stenographer working for the Canadian Pacific Railway in Moncton. She and her friend Effie Kay would run across the fields along the Dorchester Road to catch the train to work every day.

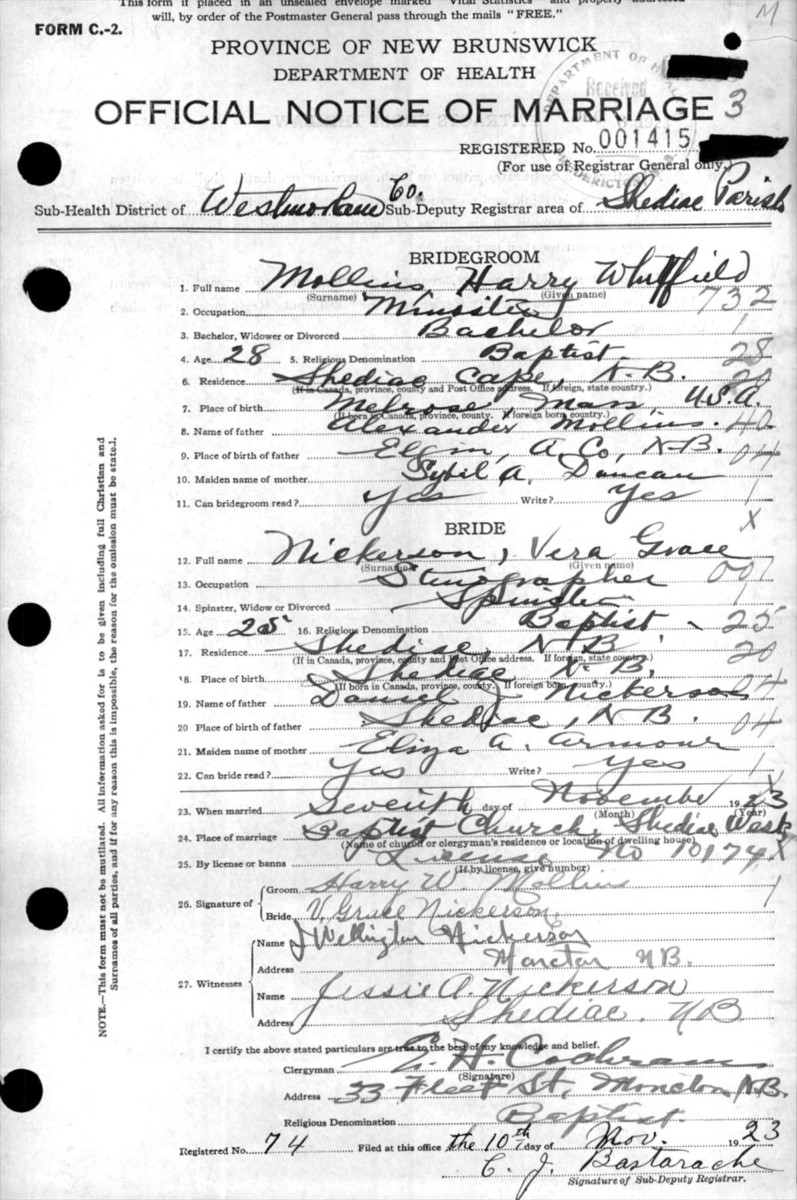

In 1923, at age 25, she married my grandfather, Harry Mollins, in the Shediac Baptist Church.

He was a Baptist minister and they moved around: from North River United Baptist Church in Westmoreland County, New Brunswick; to United Baptist Church in Windsor, Nova Scotia; to Fourth Avenue Baptist Church in Ottawa; to Park Avenue Baptist Church in Brantford, Ontario; and finally to College Street Baptist Church in Toronto.

He was a Baptist minister and they moved around: from North River United Baptist Church in Westmoreland County, New Brunswick; to United Baptist Church in Windsor, Nova Scotia; to Fourth Avenue Baptist Church in Ottawa; to Park Avenue Baptist Church in Brantford, Ontario; and finally to College Street Baptist Church in Toronto.

The College Street Baptist Church at Palmerston and College streets was converted into condominiums about 10 years ago, but at least the external heritage site was preserved intact.

My grandfather died soon after the family moved to Toronto, but my grandmother was allowed to stay in the manse, which was at 718 Dovercourt Rd., just as long as she paid the mortgage — no charity from the church for the widow and her four children, my father always said.

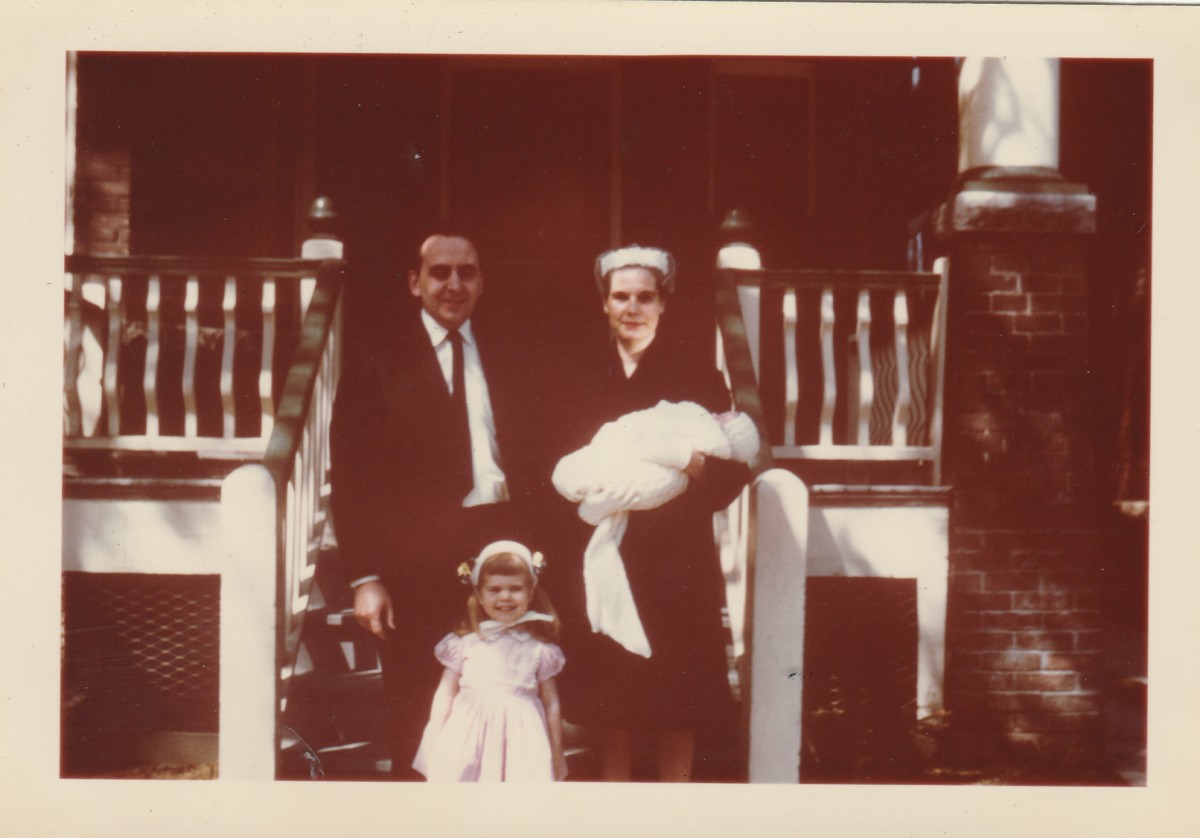

Me (as a baby) after being dedicated at College Street Baptist Church with my parents and sister outside 718 Dovercourt Rd.

Despite the tragic loss of their main source of income, the family managed to buy the house and stay in it from 1945 to 1965, partly by taking in boarders.

My grandmother was one of three widows living in a row of Victorian houses on Dovercourt Road, just south of Bloor Street. At first, the three resisted pressure from the developers to sell up and move to make way for the incursion of the horrific high rise towers that now stand where the houses once did. A developer upped his offer several times, but the widows had made a pact not to sell.

Finally, one by one they caved. The three houses were torn down and the massive building was constructed, the main entrance located exactly where 718 once was. One person on the southwest corner of the building site at Rusholme and Hepbourne streets did not sell and the house is there to this day, dominated by the great white tower.

My grandmother moved to a bungalow at 105 Castlewood Rd. in the north of the city, a sterile suburb at the time, since transformed into a neighborhood of monster homes.

International Women’s Day provides an opportunity to reflect on her life. As a senior citizen she carried on her churchly activities through the Baptist Diamond Fellowship by counselling the homeless and drug addicted. She also crocheted coasters, “lap” afghans for charity, made magnetic felt flowers and other crafts from such found objects as mini plastic milk creamer containers and plastic bread bag tags.

In later years, as her eyesight and hearing worsened, she kept busy making balls out of rubber bands, some of which are still intact today, almost 25 years after her death.

DEVELOPER WOES TODAY

I was reminded of my grandmother’s battle last week while attending a community meeting about the massive development project slated to be built where the old Honest Ed’s discount shop operated for years at the southeast corner of Bathurst and Bloor.

Horrific 24-storey towers are planned for the site. Due to pressure from the local community, the plan has been revised to include parkland and retail space. At the meeting, I observed artfully presented maps of the available zones for large-scale development in the area in red by the city planner.

The city’s position on the development appears to be based on the notion that since there are so few areas for development, this particular space should be filled with monster towers, replacing the heritage buildings and pretty street that Honest Ed Mirvish preserved.

This seems like a cop out or a “lowest common denominator” approach. It is extremely cynical to state that since we have very little land, we must build on it under the pretext of providing affordable housing when the proceeds will in reality line the pockets of very wealthy people.

Some people seem to believe that they will find cheap housing there, but even if the developer strikes a deal now with the city over the cost of rent, who is to say that they will stick to it? It’s not publicly funded housing.

I lived across from the Neo Bankside buildings in London, right behind the Tate Modern art gallery in Southwark for the four years during which they were built. Originally the developers were supposed to provide some affordable housing. Eventually, the landlords managed to wriggle out of the deal.

Those towers have lovely terraced gardens at their base, but no one is ever seen in them.

Despite the reassurances from the city planner that Honest Ed’s Alley, surrounding playgrounds and an “invisible tent-like structure,” will mitigate the impact of sky rise towers, it is highly unlikely that anyone will want to spend time in the shadow of these structures.

They will probably produce wind tunnels and be suitable mainly as a place for people to take their dogs.

From experience, I know that once the thing is built, cold hard reality will set in — the pretty pictures drawn by the architect will never be the reality and instead this development project will destroy the neighborhood. What controls will be in place to ensure that the plans do not change throughout the construction process?

I think these buildings should be at least half the proposed height of 24 floors. I’m sure when the developers put in their proposal they assumed they’d be lucky to get away with 10 storeys, so they are undoubtedly rubbing their hands in glee.

Residents in Seaton Village, Bloor West Village and elsewhere in the city have spent many years supporting the Mirvish family by shopping at their stores and attending their theaters.

My mother, Joan Mollins, ca. 1961 in Bracebridge, Ont., wearing a dress purchased at Honest Ed’s by my grandmother as a gift.

Part of that support involved a sense of pride at Ed’s efforts to preserve heritage, help artists and maintain the integrity of the neighborhood.

The community supported him and now his son, David, has apparently turned on the community by selling the parcel of land.

I suppose the city will not be satisfied until absolutely all heritage is destroyed and the entire landmass of Toronto is covered with 30 foot towers.

My grandmother, who also shopped at Honest Ed’s, died in 1992. She was almost 95.

She painted “by number” a picture that reminded her of her father’s sleigh and the fun she had when he was pulling her sled along behind him.

ALSO READ: From Neo Bankside to the Shard